This past February 20 marked 30 years since my mother’s diagnosis with breast cancer. I still remember my parents delivering the news to my older sister and me, saying the final word, “cancer,” as fearfully as if they were striking a match at a gas pump. While I didn’t appreciate their approach then, and I still don’t, I understand where they were coming from. In one of the more noticeable and persistent expressions of undiagnosed autism in my youth, I was literally obsessed with my mom – specifically the possibility of anything bad happening to her, and even more so the eventuality that she would die one day. This fear was underlined by the fact that my grandmother, my mom’s mom, died of breast cancer before I had a chance to know her.

As a young child, I was nearly inseparable from the focus of my obsession. Fortunately mom was around a lot during those early years, first as a housewife and then running a daycare and a small creative business out of our home. My dad was an executive in cable TV at the time – impressive, intensive work in the high octane culture of 1980s Manhattan – so he was largely absent from domestic life, even when he was physically present. Whenever my parents had social engagements for his work, they’d hide their plans until as late as possible because they knew it would trigger inconsolable screaming and crying from me. Mom quickly learned that isolating herself in the bathroom to get ready wasn’t enough; the telltale spritz of perfume would need to wait until she was walking out the door, otherwise I’d catch a whiff, setting off an even longer bout of unpleasantness for the whole family. The one time my parents cajoled me into letting my dad walk me to the bus stop, an unusual morning when he didn’t need to make the three-hour commute to Greenwich Village, I developed a piercing headache at the sight of the bus and was returned home instead of boarding it to half-day kindergarten class.

Growing older required more flexibility from me, but the stress impacted my physical health. I was hospitalized with a mysterious illness when I was five, and then I managed to come down with pneumonia for three weeks after we moved to sunny Florida the next year. However this began the happiest era for our family, with my parents running an editing and publishing business from our lovely home for a few years before finances required more meaningful sources of income. Mom then took her turn in the workforce, and I became her watchdog, constantly calling her office to check on her. I’d regularly eyeball the clocks until I spied our blue Ford Escort rounding the tall pampas grass on the corner of our white seashell-paved street, greeting her with relief and excitement that she had survived another day. Recently I found a note I had written to her from those days, pages and pages of post-its, saying slightly different versions of the same thing: I love you, I hope you’re safe. I love you so much. I hope you get home safe. Please be ok.

And then there were my parents not many years later, standing in the dingy kitchen of a dilapidated little rental house, telling their bizarrely emotional 13-year old daughter that her mom has the C-word the whole family has been dreading since it first took down her grandmother. But I didn’t freak out. I recall registering a simple click of acknowledgement that my brain had received the message, quite an unfortunate message, but a simple message nonetheless, one that I quickly filed away before returning to whatever I was doing before they had called us together. I ended up acting out horribly over the following two years, but I still don’t recall being acutely concerned about mom’s health during that time, not even when gazing at her puffy mastectomy wounds or watching her endure six grueling months of chemo. It was all unsettling, sure, but largely just a sea of data to be captured, organized, and stowed. Consciously at least.

The return of mom’s cancer during my junior year of high school elicited a more palpable reaction from me. We always felt a little antsy waiting for the results of her scans, and the air in our living room that Saturday told me it was bad news before my parents did. Their verbal confirmation sliced an icy metal chasm through my sternum, the place where the cancer had returned in my mom’s body, tucked deep in bone where surgery couldn’t cut it out. I was stricken to my core, and this time I knew it. The world went spinning and bumping, my brain suddenly a pair of sneakers tossed in a clothes dryer. But I was no longer the little girl physically clinging to her mom. Not after everything that had happened in our family by then. No, definitely not. So I maintained my composure in front of my parents – intentionally this time, unlike when I was 13 – politely but hurriedly excusing myself for some unexpected errand. Then I drove straight to my boyfriend, showing up wide-eyed and shaking at the big home improvement store where we both worked, tearfully babbling my terror to him as soon as he was within earshot, nevermind our audience of coworkers and customers.

I was right to be so upset; intuition for the win. Mom put up another valiant fight that lasted a few more years, but it ended when I was 20 and she was just shy of her 50th birthday. It was the worst thing I had conceived of being possible, the thing I had feared and tried to prevent my whole life, and it had happened. It was a fate worse than my own death. I’d been scared of death in general for a long time too, but I’d finally squared with it as a young teen by realizing that worrying so much about my life ending was just wasting the life that I was worried about losing, so the reasonable thing to do was stop worrying about it and just go out there and live it while I still could. How do I reconcile this though? My precious mother was taken from me too soon, before she could see me get married or meet my children. What would I do without her? My family was already tiny and broken. My dad and my sister had always been close, which made me the odd one out. I didn’t know any other female relatives, if they still existed. I’d already had such a tough road too, me and all my strange behavior and health issues. This didn’t seem fair. This really didn’t seem fair at all. So I raged. I raged against the injustice whenever I reasonably could, and sometimes when I reasonably couldn’t.

I’d been destroying myself with grief and its related trappings for several years when I finally had another epiphany about gratitude. It was around the time I became pregnant with my own daughter that I began to envision my wonderful mother and my time with her as a bountiful feast of seemingly endless delights. Except I’d always known my time with her was limited, so I’d ploughed through that extravagant banquet like I was racking up points in the bonus round of a tacky game show – greedily gobbling all the mom goodness in my path, ripping off gleaming cloches as they came near, scooping up huge handfuls from heaping platters, and mashing morsels into my face with more zeal than aim. I loved almost every dish in my mothering buffet and would gleefully proclaim my feedback to anyone – and no one – at various intervals of my indulgence, shouting out through messy mouthfuls and grinning goofily with scraps of beloved mom hanging from my teeth. I was ravenous and insatiable, slowing only periodically for my left hand to grab the nearest clock and bang it against the table with frustration until it broke. When my plate was taken from me and the table cleared — when my mom died — I cried, “No! Too early!! I want more, dammit!!!” And I cried and cried and cried… and I banged my fists, and I kept crying, crying out loud, but nobody answered me, not with words anyway. Nobody brought more or different food. The world just looked at me as I wailed and flailed, sometimes pointing a brow or rolling an eye but largely just indifferently drifting by. I sat at that table punishing myself, making a fool of myself, disrespecting myself and my mother, for quite awhile.

But I finally blew myself out. When I lifted my head from my stupor, all that was left was love and gratitude… hanging in the air all around, pieces delicately drifting down on me and the vast empty table, as if they were glistening flakes of silver snow on a silent winter day. And I finally understood. I realized how woefully impolite I had been… in how I’d been eating and talking the whole time, and especially in how I’d behaved in the aftermath. I wish I had nibbled, I wish I had savored. I wish I had better shared mom, especially with herself. And when it was all over, the appropriate response was to say thank you. To honor those who had made the feast possible, to nourish my body with its nutrients, and to bask in the afterglow of its beauty. In short, to better appreciate what I had instead of continuing to grieve its loss and the loss of what never was.

Of course, right? This approach then seemed so obvious that I next wrestled with significant guilt and shame for not having figured it out sooner. It had been several tumultuous, often embarrassing, years. Had I been too upset for anyone to talk to me about it? Why didn’t we discuss grief as a family, or figure out some bereavement plan in advance? Was it just that awful to talk to me about anything? Blargh. Topics to unpack later, but not a particularly constructive line of thinking for the moment. Applying gratitude did the trick here too. Hey, at least I got it eventually. I’m grateful to know now. Nobody knows what they don’t know. I had a lot to learn, and a lot to grieve. It’s all a process. Gratitude has become a critical key to maintaining my peace and happiness.

As those of us with autism tend to do though, especially for exciting new things, I may have leaned a little too far into gratitude and lost some momentum as a result. Since my revelation, I got so busy being properly grateful for what I had with my mom that it didn’t occur to me to try to seek out an alternative source of such guidance and support, perhaps also subconsciously inferring from other interactions by then that my mom was the only one who would ever really accept me and all my weirdness. It was as if I had built a massive bonfire of appreciation to honor my mother and became mesmerized by its warming, protective glow, only somewhat consciously aware that cunning wolves could still be circling beyond where the light ended. I was just so grateful to be grateful, so relieved from my intense pain, that I hunkered down and drifted off to sleep for a bit.

Thinking in metaphors like this is helpful for me to make sense out of situations and identify creative solutions. Here I see myself rising again, stronger and renewed. I’m building a torch from my bonfire and proceeding with new adventures, carrying some of my gratitude with me for strength and protection but no longer remaining at its monument – where I had been consciously idolizing it and my mom in all their glory, yet subconsciously, at least somewhat, immobilized by the fear of what may lurk in the shadows beyond. Even if that fear was just having something so wonderful again and then losing it, but more likely the fear that I would never be deserving of another such wonder.

In this way, despite its divine nature, gratitude can be limiting. This is particularly true if it distracts from taking constructive action, like what happened to me for a while, or under the snarky mentality of “just be grateful for what you have (and don’t ask for anything else).” These days I like to remind myself that we can be deeply grateful and still strive for more and better. All things in moderation, as my high school self loves to say even to this day. So maybe I let it go on too long, in another expression of unchecked autism, but my bonfire had become a necessary step in healing my grief. Now that I’m thoroughly warmed and better informed, I’m venturing away with my torch of gratitude, lighting new fires whenever and wherever they can help along my journey.

EDIT 5/18/2025: Updated a reference to Asperger’s syndrome to be a reference to autism.

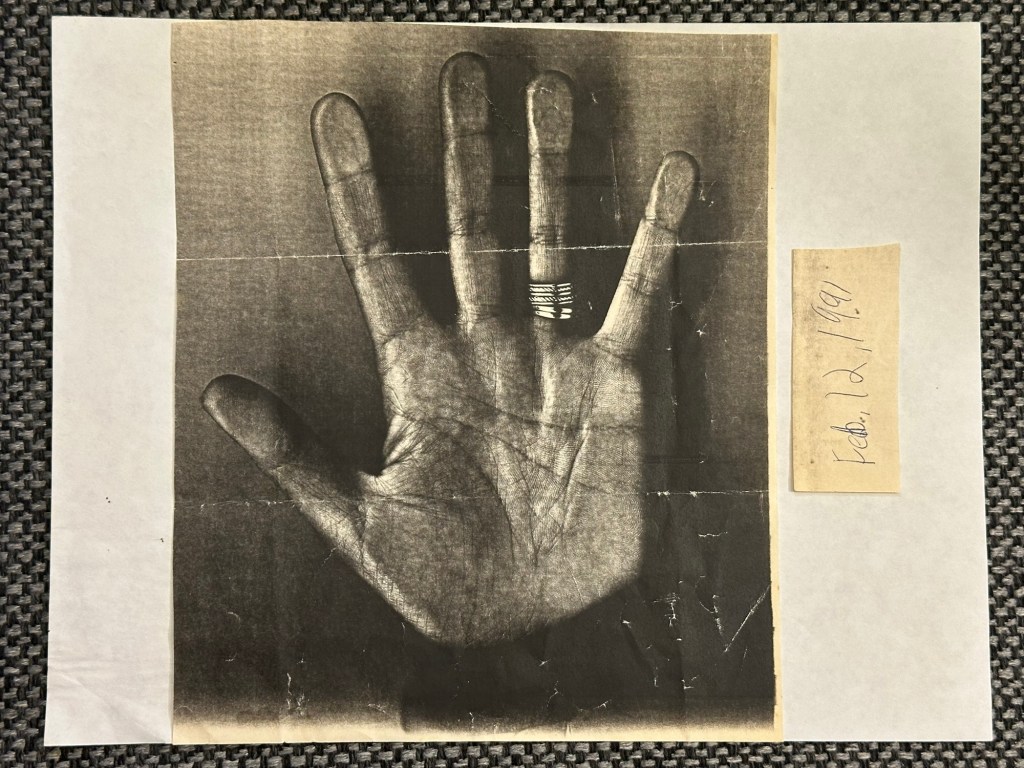

EDIT 4/18/2025: Updated the featured image to be the handprint of my mom, circa 1991. The original, AI-generated image is shown below.

Leave a comment