I had mixed feelings on using the phrase “it’s all good” when writing the statement for this blog. While the philosophy resonates with me deeply, the words have a ring of toxic positivity to them, and that’s definitely not our vibe here. I’m well aware that being alive involves plenty of things that don’t qualify as “good” as we experience them: broken dishes, headaches, and parking tickets are some of the more mundane examples; bankruptcy and divorce are heavier ones. But I can categorize all that negativity as “good” in an ultimate, overarching sense because it represents potential catalysts for positive change, or it’s simply necessary in this beautiful, mysterious, ever-evolving existence we’re all sharing and creating together, where nothing tangible is meant to last forever.

Anything we deem to be “not good” is generally viewed as such because it elicits some variety of pain, whether physical or emotional, conscious or not. And understandably most properly functioning humans seek to avoid pain, but it’s a valuable instructor when we encounter it. Individually, we know pain teaches us not to touch the hot pan on the stove with our bare hands, or if we have a scrape on our leg that needs tending. Pain also teaches us how to be stronger by exposing a weakness in ourselves, when cutting our finger in the kitchen informs us to sharpen our knife skills or polish our focus. Emotional pain, such as embarrassment, can tell us not to trust our rowdy new friend so fast, or to tighten up our elevator pitch. In this way, each pain is an invitation to learn for anyone who is ready and willing to heed the lesson that is inflicting the pain. Not all of pain’s lessons are significantly negative, either. Depending on the nuances of the sensations we receive, a simple pang in our stomach could be telling us that it’s time to eat or to find the nearest restroom. And not all pain lies within the individual. Unchecked pain compulsively spreads itself, creating interpersonal and collective pain.

Pain shared between two or more people could look like an angry shouting match, a disrespectful spouse, or a stolen identity. On a bigger scale, it takes the shape of things like war, genocide, and systemic corruption. In all these arenas, pain teaches not just individuals but also pairs, groups, and society at large – anyone involved in that specific pain experience. When we reveal our pain to each other with hurtful or otherwise seemingly inappropriate behavior, it’s an opportunity to learn about ourselves and each other. Was a wrong truly committed, and if so, by whom and why? What are the other factors? How do we move on, and if we want to prevent similar occurrences in the future, how do we do that? This process better informs us about who we are, what we’re willing to accept, and what we strive to be. It has been part of our natural evolution as a civilization to be constantly challenged by each other’s behavior. As we collectively evaluate significant shared experiences, we build on the lessons from the past. With each new pain, we decide if we want to take the invitation to change something about the way we’re operating, or if we want to avoid the work of progress and risk repeating the lesson or getting a worse one.

The pain we experience generally finds its roots in some sort of loss, whether it’s the deep pain of losing a loved one at their life’s end, the physical pain of losing some of our own health to the flu, or the annoying pain of losing our patience in rush hour traffic. We can choose to lose without being pained, though, much in the way Buddhist principles tell us we can experience pain without suffering. The power comes from changing how we think. Loss is a part of all natural cycles, from cell apoptosis and abscission to ocean tides and supernovae. So we love loss and the role that it plays; it’s instrumental to reality as we know it. The goal then is not to avoid all loss, but to reasonably protect against what we can and then “lean into” the rest by preparing for it and managing it. This includes formal activities such as succession planning as well as less tangible efforts like mindfully appreciating what we have while we still have it. And when loss does strike, this also includes allowing for grief.

While painful in its own right, grief too is “good” in the sense that it’s a natural and necessary response to healing from loss. Skipping this step can lock up our pain which we then carry with us as emotional baggage, invisible and often consciously forgotten but weighing us down all the same, insidiously reducing the quality of our well-being, functioning, and relationships. And grief is a far easier pill to swallow when it isn’t studded with the prickly regret of what could have been or ballooned by the fear of what might be now. When grieving becomes more complex, when it’s unreasonably difficult to be gracious after something valuable is gone, then we’ve found a ripe opportunity for meaningful personal development or spiritual growth – another gift.

Of course, we don’t want to take all the opportunities that are presented to us. Some don’t feel right, sometimes we aren’t ready. And in the grand sense, we know it would be impossible to take them all even if we wanted to, as taking one opportunity inherently closes down the possibility for others. So we want to watch which opportunities are earning our time, energy, and attention, and what we’re gaining from them. It’s easy to pass up the chance to process thoughts of a painful breakup when we’re compelled to peruse cute new workout clothes on Instagram. But when we miss an opportunity to work through our pain, we don’t learn the valuable lesson that inflicted it in the first place, so we’re all but guaranteed to keep getting similar invitations. The process is generally more discreet than the envelopes that flood Harry Potter’s home when it’s time for him to attend school at Hogwarts, but it can be no less intense. That’s okay too though; everything in its own time.

Time alone is not enough though. The old saying “time heals all wounds” is true but only when factoring in the efforts exerted and perspectives acquired over that period. Time alone does not heal; it forgets, it layers, it buries. It’s effort and perspective that are the healers, the ones who help us ultimately see everything as good. The effort comes in the form of working through one’s pain responses as we’ve noted, but perspective is a little trickier. Sometimes we’re too involved in a situation to see it for what it is, like standing too close to a painting and knowing the colors but not the image. Other times we are much too far away to glean even the slightest detail, yet we may find ourselves forming strong feelings or opinions nonetheless. And to complicate things further, it can be nearly impossible to know for sure how much we do or don’t know in any given situation.

Reality is like one of those infinitely zooming images where we can keep finding information wherever we focus our thoughts, yet we’re constantly seeing static pictures as we go about daily life. This dynamic is necessary for efficient functioning, like compressing a file before emailing it; society would struggle to get anything done if we were all constantly falling down rabbit holes of deep thought. However it’s very helpful to remember that the vast majority of what we perceive is simply a veneer, and the more we peel back layers to understand, the more we see goodness and find peace. But “bad” behavior is still “bad” as it happens – so while there are reasons for just about everything, there are excuses for just about nothing. And properly holding people accountable for the wrongs they commit is one way we make “good” out of “bad.”

This transformative work sits at the core of our existence. This is why it’s all good: for all of us to be the audience, actors, directors, producers, and stage crew, all at the same time to varying degrees, crafting some big drama of our choosing. How can that process be anything other than good and beautiful? We’re collectively shaping our shared reality with our actions and beliefs. If we’re unhappy with the results, then we can adjust our perspective, heal and prevent unresolved pain in ourselves and each other, and truly appreciate what we have while seeking more reasonable solutions that work better for everyone. Because the more of us who believe it’s all good, the more of us who see reality for the good that it is, the more clearly others will be able to see it too. And the more we all see it and look for it, the more goodness grows.

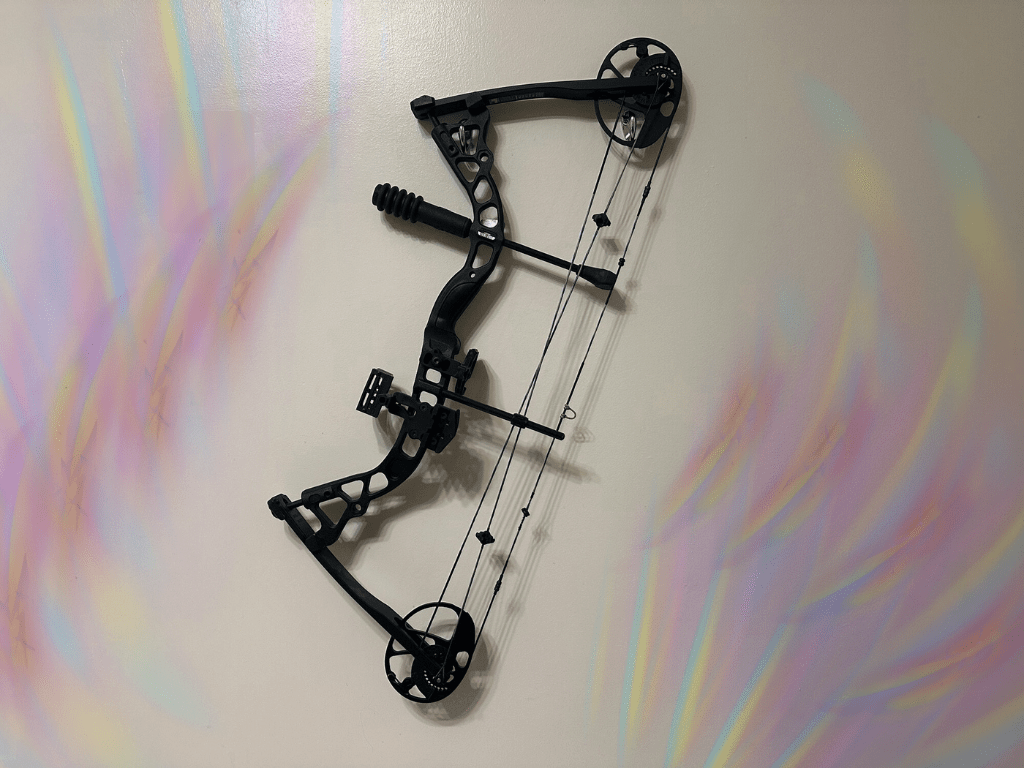

EDIT 4/18/2025: Updated the featured image to be a sketch I drew when I was 19 years old. The original, AI-generated image is shown below.

Leave a comment